APRIL 18, 2008

Red, White, and Blueberry

Reviewed: The Flight of the Red Balloon,

My Blueberry Nights

By Mark Jenkins

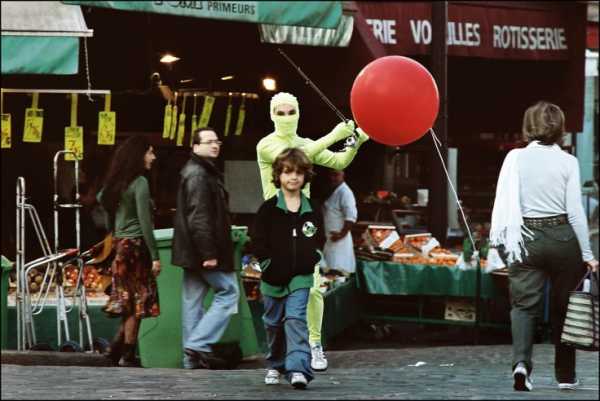

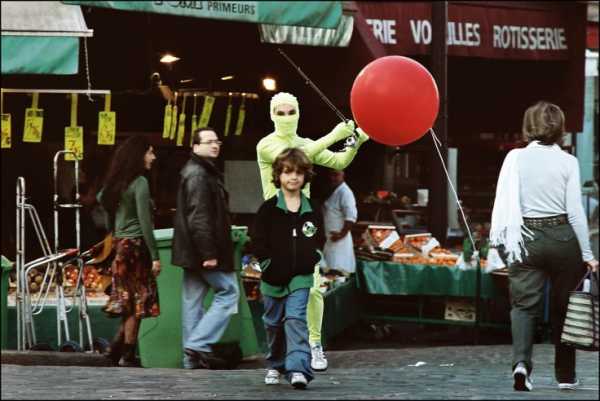

The West is Red: The Red Balloon follows Simon Iteanu. (IFC)

Also this week: reviews of THE FORBIDDEN KINGDOM,

THE VISITOR, WHERE IN THE WORLD IS OSAMA BIN LADEN?,

and THE SINGING REVOLUTION and interviews with the director and musicians of YOUNG@HEART

A FILM THAT CAN BE READ as either enchanted or ominous, Albert Lamorisse's 1956 The Red Balloon is unquestionably a tale of childhood. A Parisian boy bonds with a balloon, which ultimately rescues (or abducts) him. Taiwanese director Hou Hsiao-hsien's visually exquisite homage to Lamorisse's fable features a boy and a balloon, yet is hardly a kids' movie. While mop-topped, 7-year-old Simon (Simon Iteanu) is present throughout THE FLIGHT OF THE RED BALLOON, he's upstaged by his frantic, bleached-blonde mom Suzanne (Juliette Binoche) and other highstrung adults. He's also less prominent than his Chinese nanny, a puppet troupe, and — this being a Hou movie — some thrillingly graceful long takes.

Simon goes to school, plays games, and remembers summer visits from his teenage "pretend sister" (actually his half-sister). In one poignant (and seamless) transition, Louise (Louise Margolin) emerges from the boy's memories and into a flashback. Simon loves and misses Louise, as does her mother. Suzanne hopes to evict her downstairs tenant, a onetime friend who's stopped paying rent, to make room for her daughter. But Louise may not relocate from Brussels to Paris, just as Suzanne's writer boyfriend may not return from Montreal.

Meanwhile, Suzanne has hired a new nanny, Chinese film student Song (Song Fang, effectively playing herself). Song supervises and escorts Simon, and also helps his mother with her work. A voice actress for a puppet theater, Suzanne is devoted to Chinese puppetry and its stories. (Among Hou's previous films is 1993's The Puppetmaster, which surveyed Taiwan's history under Japanese colonization through the career of its title character.) Song is making her own version of The Red Balloon, using up-to-date video trickery. A red balloon appears in the opening scene, then vanishes for almost an hour. When it reappears, it comes not to save Simon but just to observe him. It even watches as he, on a class trip, contemplates Felix Vallotton's painting of a child and a red ball at the Musee d'Orsay, Paris's storehouse of Impressionist canvases (which commissioned this film).

One of Hou's trademarks — borrowed by the chameleon-like Ang Lee for Lust, Caution — is the contrast between stately compositions and eruptions of messy violence. There are no fistfights or knifings in The Flight of the Red Balloon, whose characters are mostly artists, craftsmen, or children. But there is anger and chaos, especially in Binoche's semi-improvised dialogue. After the scenario was conceived by Hou (who's not fluent in French) and co-producer Francois Margolin, the lines were invented by the actors during rehearsals. (Binoche even takes two "solos": one-sided telephone conversations that are virtuoso performances.) The result seems naturalistic, yet the action is precisely choreographed. Several scenes conveying the emotional clamor of life in a cramped Parisian apartment, full of family and visitors, proceed from character to character, situation to situation, without a single edit.

Aside from Binoche's expansive character and captivating performance, what carries the film is its visual style. The color and motion are extraordinary. There are many inserts of trains — a Hou obsession that he shares with Japanese director Yasujiro Ozu, the inspiration for his previous film, Cafe Lumiere — and a sequence in which Simon's ride on a carousel becomes nearly abstract. Hou and longtime cinematographer Mark Lee Ping Bing (who also shot much of Wong Kar-wai's In the Mood for Love) include a lot of rich reds and oranges, but the family's kitchen is a shade of aqua that they seem to have retained from Hou's films set in Taiwan, notably Millennium Mambo.

With its Satie-like score and use of Paris's iconic skyline, the film has a strong sense of place. Yet it also keeps some distance from its setting. Unlike Wong's My Blueberry Nights, which attempts to be all-American, The Flight of the Red Balloon acknowledges that it's about Western life, but not of it. If Suzanne is the central character, Song is the director's on-screen surrogate, as much the bemused observer as is the camera. Inevitably, the result is a movie that lacks the passionate engagement of Hou's films inspired by Taiwan's history or his own life story. Still, there are moments that are as moving as the images are lovely. Hou may be an out-of-towner, but he quickly finds his place, crafting a film that elegantly balances local color, universal emotions, and subjective viewpoint. (2008, 113 min; at Landmark E Street).

WONG KAR-WAI HAS BEEN LOOKING for an escape route for years. With Hong Kong's independence scheduled to end in 2046 — thus the title of his previous feature — the director has lugged his camera to Argentina, Taiwan, Thailand, Cambodia, and even mainland China. (That last trip didn't work out.) Now he's made an American movie, a scenic ramble from east coast to west with occasional layovers at diners, bars, and heartbreak motels. With its vivid colors, cluttered foregrounds, and drowsy tracking shots, MY BLUEBERRY NIGHTS sure looks like a Wong Kar-wai picture. Yet it's mostly veneer, without the feeling of the director's best films.

Wong is known for fetishizing songs, both as movie titles — In the Mood for Love, Happy Together, As Tears Go By — and as fragmented, recurrent motifs. So it's no surprise that he recruited a singer, Norah Jones, as the native guide for his first English-language film. (Chan Marshall, aka Cat Power, also has a small role.) Jones plays a woman whose nickname changes at each stop on her westward odyssey. She's Elizabeth in New York, where she learns that her boyfriend is cheating on her, and consoles herself with blueberry pie at an improbable diner with a Russian name and a solicitous British proprietor, Jeremy (Jude Law). Elizabeth becomes Lizzie in Memphis, where she watches the marriage of Arnie (David Strathairn) and Sue Lynne (Rachel Weisz) move from estrangement to catastrophe. Then she switches to Betty in Nevada, where she meets Leslie (Natalie Portman), a cocky gambler whose central screwed-up relationship is with her (unseen) father. Meanwhile in Manhattan, lovelorn Jeremy tries to contact Elizabeth, and has a brief, bittersweet visit from his ex (Marshall).

Wong, who co-scripted with crime novelist Lawrence Block, doesn't seem especially interested in the U.S., and he and cinematographer Darius Khondji appear unmoved by the sweep of the American West. (The big skies barrel by in fast-mo.) The biggest problem, however, is casting: Jones is amiable but one-ply, and too much dialogue is invested in explaining why the pie man is from Manchester, or how the improbable couple of Arnie and Sue Lynne came to be. (At least the filmmaker is having a little fun with these two: Arnie is a amorously fixated cop, a trademark Wong type, and Sue Lynne's name could be spelled Su-Lin.) Portman's Leslie is the most robust character, but her principal foil is the bland Jones.

Perhaps this is too wide-open a country for Wong, who in the past has rarely moved beyond the range of neon illumination. Or maybe commercial considerations forced him into alien emotional territory. Still, solutions to all the movie's dilemmas can be found in the filmmaker's previous work. My Blueberry Nights is set in the wrong time, and outfitted with the wrong sensibility.

Most of Wong's best films evoke the early '60s, a time when Hong Kong crackled with the tension between sensuality and propriety. Much the same was true of the U.S., and there are elements in this movie — which abounds with convertibles, sunglasses, and old-fashioned hangouts — that are deliciously retro. Yet the story is clearly set in the anything-goes '00s, an age of serial monogamy rather than unrequited love. It's a world in which people are more likely to shrug than smolder, which undermines the director's obsessive style.

With rare exceptions — such as the frothy second half of Chungking Express — Wong's movies assume the viewpoint of male romantics, soft on the inside no matter how rugged their exteriors. My Blueberry Nights doesn't know what to make of Elizabeth, and there are moments in the film — notably one in which a fetchingly unkempt Sue Lynne slinks through the joint where Lizzie tends bar — that don't even attempt to represent her outlook. Lizzie stares at Sue Lynne, but the eye behind the camera is clearly masculine.

This is not Wong's first film set in the Americas. The bulk of Happy Together transpires in Argentina, although the story returns to Asia for its coda. But the protagonists of that tale were from Hong Kong, and thus viewed their new locale from the same perspective as the director. In interviews Wong has said he could make a film anywhere, so long as he took the vantage point of an outsider. Yet this movie attempts to get inside Elizabeth's America, land of such museum-piece attractions as pie a la mode, mom-and-pop casinos, and automotive tail fins. It looks great, but a lot less real than the director's impressionistic Hong Kong. If Wong's gift is to show how glimmering surfaces reveal emotional depths, My Blueberry Nights reveals that this formula succeeds only when the lovingly photographed facades have personal meaning. (2008, 90 min; at Landmark E Street).

My Blueberry Nights

By Mark Jenkins

The West is Red: The Red Balloon follows Simon Iteanu. (IFC)

Also this week: reviews of THE FORBIDDEN KINGDOM,

THE VISITOR, WHERE IN THE WORLD IS OSAMA BIN LADEN?,

and THE SINGING REVOLUTION and interviews with the director and musicians of YOUNG@HEART