MAY 30, 2008

Taking the Fall

While The Fall plunges into bitterness, Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull just stumbles

By Mark Jenkins

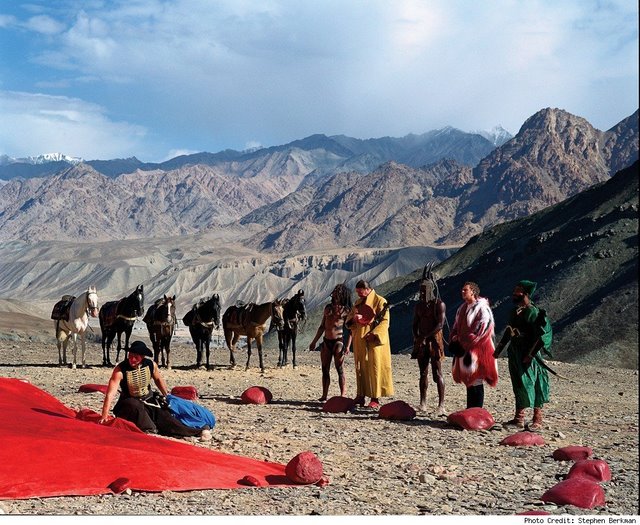

The not so great outdoors: The heroes of The Fall on one of its many locations (Roadside Attractions)

WITH MOVIEHOUSES IN MORTAL COMBAT against the I-Pod Nano, this summer's adventure flicks emphasize visuals that won't display well on a two-inch screen. Shot in 18 far-flung nations, Tarsem Singh's THE FALL is stuffed with scenic wonders and architectural marvels, both real and simulated. And while it was filmed entirely in one country — the U.S.A., land of the abashed dollar — Steven Spielberg's INDIANA JONES AND THE KINGDOM OF THE CRYSTAL SKULL flaunts its locations, from lost cities to vast waterfalls to Ivy League libraries. Yet of all the pictorial flourishes, the most telling one comes at the very beginning, when the image shifts from Paramount's alpine logo to a similarly shaped gopher mound. That's just what the drab Crystal Skull does: make a molehill out of a corporate mountain.

Whether they're about kung fu pandas or aging archaeologists, most mass-appeal pictures these days are essentially kids's movies. That trend started with Raiders of the Lost Ark and its older, somewhat smarter cousin, Star Wars, both of which drew on fast-paced, slow-witted 1930s serials. Crystal Skull continues in that juvenile mode, even if star Harrison Ford's advanced age does require the occasional mention. The adult-aimed in-jokes serve the same function as the ones in Disney cartoon features, keeping grownups's attention while contributing nothing essential to the plot.

The Fall, the years-in-the-making film from the director of The Cell, also plays like a children's movie. Yet its violence, narcotic references, and bleak denouement indicate that it's meant for some sort of adult audience. Think The Princess Bride or Time Bandits, but with a darker outlook and a significantly less humorous spin. Filmed in such exotic climes as India, China, Egypt, and Cambodia, The Fall shows a wonderful world. Yet the dazzling vistas just frame a dingy, despairing fable.

Shot for glistening shot, The Fall puts the muddy-looking Crystal Skull to shame. Still, the two share a few things, notably contrived storylines and mutual obsessions with Hollywood's past. The Fall's wraparound story is set during the silent-film era, when a stuntman who was crippled on the job spins a tale for a fellow hospital patient, a young immigrant girl who broke her arm while picking oranges. (America's dreams, you see, are made by unseen victims.) The inner tale's elaborate but uninvolving plot involves an ex-slave, a heroic bandit, Indians (both types), and Charles Darwin, and all the characters are — in the manner of the Wizard of Oz — based on people glimpsed around the hospital. Imagination can transform the ordinary into the fantastic, Singh proposes — which is not an especially imaginative idea.

A former TV-commercial and rock-video director, Singh has enlisted a style-conscious crew, including costume designer Eiko Ishioka, to craft a universe of bluest blues and reddest reds, most mountainous of mountains and most tropical of tropics. (Plus a swimming elephant.) But unlike the Great Wall of China, one of the many landmarks glimpsed as the imaginary heroes trudge toward their sour destiny, Singh's constructions have no structural purpose. Adapted by the writer-director and two co-scripters from Yo Ho Ho, a 1981 Bulgarian film, The Fall is sheer spectacle.

The story might be best appreciated while in an altered state, although that's not why the stuntman, Roy (Lee Pace), implores little Alexandria (Catinca Untaru) to filch some morphine for him. He intends to commit suicide, a goal that's reflected in the story he tells her. When the noble outlaws finally reach their nemesis's castle, doom is their likely reward. Even the questers's monkey mascot is at risk, a touch that alone justifies the movie's R rating. If this is a kids' movie, it's only for tykes with a precocious acceptance of mortality. Death is the end of every person's story, but that's a perverse moral for a fantasy epic bursting with visual life.

NOBODY IMPORTANT DIES, of course, in the PG-13-rated Crystal Skull, whose roster of anonymous victims substitutes Soviets for Nazis and Amazonian natives for Arabs or Indians. As almost everyone knows by now, the fourth installment in the Indiana Jones saga introduces its namesake (Ford) to his youthful likely successor, Mutt (dreary Shia LaBeouf), and sends them both to Peru. The search for the skull encompasses ancient ETs, an addled former colleague (John Hurt), a double-dealing pal (Ray Winstone), the reappearance of Indy's Raiders squeeze (Karen Allen), and a KGB she-wolf with psychic powers (Cate Blanchett, demonstrating that Katharine Hepburn isn't her campiest impersonation).

As similar as it is Indy's first outing, Crystal Skull differs in three crucial ways. The simplest is the use of CGI; although Spielberg has declared his enduring love for celluloid and miniatures, many of the film's special effects are digital. (In the most movie-movie one, Indy parts the red sea — of ants.) More significant is the picture's dabbling in Cold War politics. Where the earlier movies were reflexively pro-American, this one has Indy hassled by two of Hoover's Commie-obsessed boys, and blacklisted from an unidentified Connecticut college. The narrative dissonance here is that, according to David Koepp's script, Hoover was right. The reds aren't just stuffing secret cables in their vests at the State Department; in the opening sequence, they don U.S. uniforms, kidnap Indy, and compel him to search for an extraterrestrial artifact in an Army warehouse near a Nevada A-bomb test site. By comparison, the Cuban Missile Crisis was a minor provocation.

Aging Indy into the 1950s doesn't just allow the movie to open with "Hound Dog" and introduce motorcycle-riding Mutt — unpersuasively — as a wannabe Brando. It also shoves the swashbuckling archaeologist into a more complicated cinematic world than the one inhabited by his earlier selves. Where Raiders and Temple of Doom simply (if unwisely) accepted the xenophobia of '30s serials, Crystal Skull can't pretend to take seriously the Red Menace or Erich Von Daniken's theories of civilization coaches from outer space. So the movie is forced to be ironic, which throws off its stride. Crystal Skull trips over lousy lines — this is a movie that offers "I like Ike'' as a witty retort — and suffers repeatedly from poor timing.

Whether you liked Raiders of the Lost Ark or not — and I didn't — the movie was at least internally consistent. Men were men, white was right, and Nazis deserved whatever they got. In the messier postwar world, however, Indy just doesn't make sense. If he has to dig for magical artifacts a fifth time, the best strategy would be to stick him in a time machine and send him to a simpler era. Indiana Jones in the 1960s, with references to JFK and homages to Godard and Antonioni, is something nobody needs to see.

The Fall (2006, 118 min; opens Friday, May 30 at Landmark E Street and Bethesda Row)

Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull (2008, 123 min; opened May 23 just about everywhere)